One of the libraries that I work on as part of OpenYou is libfitbit, an access library for the FitBit pedometer device.

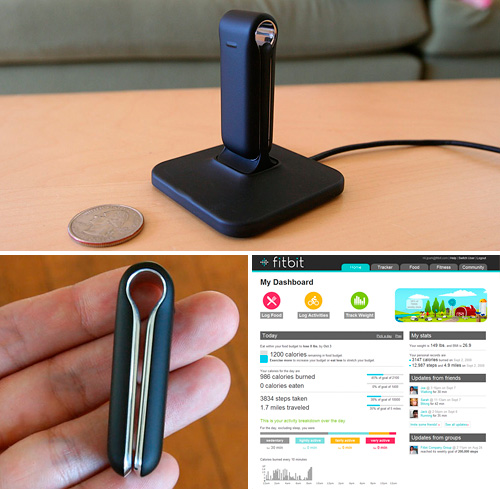

It's basically a tiny accelerometer that clips to clothing to work as a pedometer. It can also communicate wirelessly with its base station, so that whenever a user walks by their computer and assuming they have the Fitbit server software running, it'll automatically sync. The data is stored on fitbit's website (shown above, lower right), where they give you a nicely designed interface to see it, compare to friends, and for a fee, have it analyzed by on staff trainers.

The hardware itself is very well designed. In 3 months of having the device, I have yet to lose it (which is a small miracle), and it stays clipped to clothing. The battery seems to last pretty much forever, and the display is nice and crisp. The wireless has quite a range too, picking up the device while I'm in other rooms.

The problems began when it didn't have drivers for syncing via linux. Doing what it is I do, I figured I'd whip some up real quick. This is where things when horribly, horribly wrong.

(For those that want to skip the story telling version of this and just read the hard technical details, the reverse engineering document is available on the repo, which has all of the gritty technical details.)

The first thing I normally do when looking at new hardware is to check out what I can about the software that ships with the device. There's usually some logs around to help out. In fitbit's case... Well, the logs are beyond helpful. They're scary. Here's a chunk from the beginning of one of them.

01/28 23:31:55 Sending 4357 bytes of HTML to UI...

01/28 23:31:55 Processing request...

01/28 23:31:55 Waiting for minimum display time to elapse [1000ms]...

01/28 23:31:56 Waiting for form input...

01/28 23:31:57 [POWER EVENT] POWER STATUS CHANGE

01/28 23:32:04 [POWER EVENT] POWER STATUS CHANGE

01/28 23:32:14 UI [\.\pipe\Fitbit|kyle]: F

01/28 23:32:14 Processing action 'form'...

01/28 23:32:14 Received form input: email=[USER UNENCRYPTED EMAIL HERE]&password=[USER UNENCRYPTED PASSWORD HERE]&[other stuff]

01/28 23:32:14 Connecting [2]: POST to http://client.fitbit.com:80/device/tracker/pairing/signupHandler with data: email=[USER UNENCRYPTED EMAIL HERE]&password=[USER UNENCRYPTED PASSWORD HERE]&[other stuff]

01/28 23:32:14 Processing action 'http'...

01/28 23:32:14 Received HTTP response:

Yes, that's a user's email and password, unchanged and in clear text, being flung over to their website via a pure http connection. This step is also logged to the user's hard drive in a clear text file, that is world readable.

This is bad.

The log goes on to verbosely record everything the fitbit says to the website and vice versa. Fitbit sends all commands from their website to the device, meaning they never have to upgrade their client software, though firmware does have to be updated on the device every so often. This policy is actually an interesting move. It made it way easier for me to replicate how their client works for libfitbit, but also keeps them from having to update their client when they make new firmware.

To continue the fun, we move onto the promiscuous base stations. As a convenience measure, any Fitbit tracker device (the thing you wear, lower left in the picture above) will sync with any base station (the part that connects to the computer, upper portion of picture above). This means that if you're at a friend's place who has a fitbit, the device will sync, without you having to do anything.

However, in order for the information to go from the user's fitbit that's attached to them, to their account on the website, there has to be some identifier on the device to let the website know who's who. The tracker serial number does this. The first thing the website asks for is the tracker number, and it then returns the user ID associated with the tracker number. The user ID is what's used to access a profile page, i.e.

http://www.fitbit.com/user/[user_id]

After knowing the combination of user id and tracker serial, anyone can be basically authenticated and can send data to the site under the account the tracker is bonded to.

This is an incredibly easy system to spoof. I could walk around with a netbook and a fitbit base station in my backpack, gather serial numbers at a public meetup, then have all the account information I wanted.

Which brings us to the crux of the problem, and the reason I believe the software is the way it is currently: Why would I do that?

It's just steps, after all. Who cares?

This is one of the things I'm seeing more and more when reverse engineering medical hardware. It's not financial information, it's not important health information, so why should it be locked down?

While this may seem like a rather light issue (other than the password in the clear thing, which is 100% inexcusable), with common thought being 'woo, someone stole my steps!', the implications can get pretty staggering depending on how far out we want to cast the timeline, especially in relation to device popularity.

First off, one of the major marketing points of QS hardware right now seems to be synergy between information stores. Fitbit can now instantly upload a user's data to DailyBurn, Google Health, and other sites that the user links to it. This is considered a value-add for health hardware, since users may have been keeping information elsewhere before whatever device they're using existed. This also means that if I have write access to one account via the methods described above, I have write access to many accounts via account bonding across sites, assume the user has created those bonds.

To crank the paranoia level another notch, the amount of device companies I've talked to that are also looking at linking to health insurance companies really makes this a horror story. If someone maliciously gets into a user's health device account that then links into health insurance/health care, who knows what havoc could be wreaked.

Finally, there's lots of metadata that can be lifted from these devices as more and more of them go wireless. If you're wearing something that uniquely identifies you, that means all someone needs is a base station to tell who the user was, where they were, and when. In the days of geolocative apps and constant check-ins, there comes the question of whether people might want that implicitly, but this seems like it should be opt-in versus opt-out (or in this case, no opting at all).

So, yeah. Fitbit is a great design, and completely insecure, though not unfixably so. Everything I've talked about above could be easily fixed. Flip on https for transfers (but please don't encrypt everything, as I'd like my drivers to keep working), don't log everything ever to disk, allow users to set whether they want base sync promiscuity or not. It's not that bad. However, the fact that this was even seemed like a good idea in the first place is a bad precedent for health hardware to come.

And all I wanted was a pepsi some linux drivers.